A Bit Is A Bit Is A Bit. Or… Is It?

Much of the following content was originally included within my article regarding ifi’s Nano iUSB 3.0. I’m now publishing as a separate piece to use as a basis for general reference, and as a background to be linked within subsequent reviews of digital conditioners, reclockers, etc.

Introduction

One of my most “interesting” discoveries for me has been that a high end, high efficiency IT system (e.g. an hi-tier Laptop) can be quite far from being an ideal platform for an apparently “light” data transfer activity such as streaming digital audio from where its passive containers (the FLAC or WAV files) are, up to a USB-connected DAC.

The first and simplest perplexity an IT enthusiast, or specialist, comes up with when confronted with the above statement is some variation of:

“Cmon… A bit is a bit! The PC just has to transfer a digital file to a digital device, via a digital interface. Don’t tell me you ‘hear’ deterioration in the process as there can’t obviously be – data will not deteriorate!”.

Of course it’s exactly like that.

A bit is a bit, and the very same bits stored into (say) a FLAC file onto the PC’s hard disk will reach the externally connected USB DAC once sent over. No doubt. No error.

Too bad that this is not the point.

Cables as trojan horses

DACs are devices supposed to take such digital data (FLAC or whatever files) and convert their contents “on the fly” (i.e., while still receiving them, one little chunk at a time) into analog data (i.e. the music we all want to enjoy).

So far so logic. The problem is that a few unobvious caveats apply.

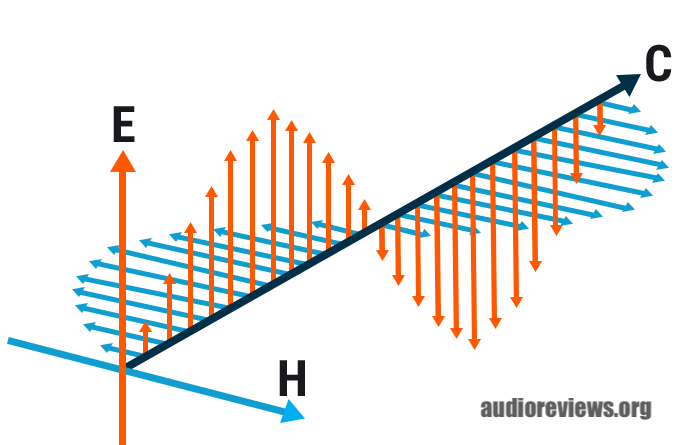

First of all it’s important to understand that while EMI (Electro Magnetic Interference) and RFI (Radio Frequency Interference) investing, say, a laser printer while printing a Word page on paper is not going to significantly (or at all) change the quality of a 600 dpi printed text, DAC chips and the rest of the circuitry around them will change (and significantly so) their behaviour, and ultimately reproduce “different sounding music”, when subject to EM/RF (and other) perturbance.

And no, it’s not enough to protect (“shield”) the DAC against perturbances in the human audible frequency ranges (20-20.000 Herz give or take) because this all is not about preserving the DAC’s job result after it was obtained, rather it’s about making sure the DAC is not “disturbed while doing its job” (simplistically said).

The bad news is in facts that DAC chips, and the electronics “around” them inside the box are sensible to frequencies up to a few Giga herz (!), which can sadly come from a virtually infinite spectrum of possible origins.

“Well then this is mostly about properly shielding the physical DAC box, so any possible “waves” polluting the environment near my DAC will not get in, no? Is this why I often read that a desktop device will most often be better than a mobile one?“

Sadly, no.

Or yes, of course you would ideally want a “nicely shielded dac box”. And yes, this is (normally) an inherent advantage desktop systems have over portable ones. That’s quite logical. But not enough.

Seriously pernicious interference can first of all come from the DAC’s power supply itself.

Converting from Alternate Current (supplied by the wall outlet) to Continuous Current (required by the DAC electronics to work) creates in general “side effects”, which are nasty for our DAC, and are transported into it by the very electrical cable which is needed to feed it with the “good part” of its required power.

Ideally, we would want:

- a “side effect free” Power Transformer, to generate an as apriori-pure CC as possibile, and

- shielded power transport cables to avoid “collecting noise on the go”.

Furthermore: the USB cable is another trojan horse for noise – and the more so if the same cable is used to carry both data and power into those DACs that do not have a separate input port for an independent power supply.

A PC 99.9% of the times has not been designed with audio-grade EMI/RFI prevention in mind, for the simple reason that it won’t be required by 99.9% of its uses.

All sorts of “bad waves” (I’m again vulgarising here) do happen inside the PC, and do indeed propalate out via any connected electrical conductor – there surely included the USB cable, the same on which our “a bit is a bit is a bit” data is unawarely travelling.

Timing is vital

Should the above (vulgarised) scenario be not enough, there’s even more to take care of. Again, I’ll make this a bit simplistic but give me some rope here, or wordage gets too complicated and it all’d get even worse 🙂

Data communication between a PC and another PC, or between a PC and a HD for example, are designed to be “as quick as possible”, while not necessarily “as time-regular as possible”.

While saving your Word file from your PC memory to your HD the actual writing speed might vary during the process as a consequence of many factors (your PC doing something else at the same time, the HD receiving other files at the same time, the HD speed recalibrating following thermal variations, etc etc etc). Depending on what actually happens, your file will save like one tenth of a second faster or slower. Who cares…

In a very bad case a peak of interference will force a data packet retransmission: a full second might be lost in the process (how bad!…). What really matters though is that no quality difference will be there at the end: our file will be “perfectly intact” on the HD.

Not the same applies when the “receipient” is a DAC.

Audio devices require to receive digital data on a perfectly timed schedule. Otherwise (guess what?) the DAC being unable to autonomously correct such schedule, it will convert data at the “irregular” pace with which it receives them, and the result will be “different music” than expected.

Data flow into the DAC must follow a sort of atomic-clock-precision “metronome”.

Now guess what else: when you connect an external DAC to a PC via USB, the default choice is using the PC’s internal “metronome” (called “Clock”), which – you know that by now – is sub-par for our audio purposes as it never was designed with the level of accuracy, and never equipped with those pace-granting gimmicks a DAC desperately needs.

Furtherly, even when the PC and the DAC “somehow manage” to adopt an adequately reliable clock to keep data flow pacing as regularly as the DAC wants, internal PC EMI/RFI can – and will – screw timing up every now and then anyway. And, DAC chips in general don’t come with built-in “circuitry” capable to correct such “hiccups” on the fly.

Lastly: as pacing is so important each DAC has its own independent metronome clock generator inside, used to master the timing of all its internal operations. A similar little device (“oscillator”) than the one used inside the PC generates that, just a more precise (and expensive) one. Too bad that such device is an electrical device like all the rest inside there, so should inbound power supply be not perfectly clean… yes, you guessed it 😉

What a mess. What can we do?

Well very simply put what I just tried to say until now tells us that first and foremost a “generic” IT system (a PC, a Laptop…) is for a number of reasons far from being an ideal choice as an “audio player” when audiophile-grade results are wanted.

To solve the problem there are three possible conceptual approaches

- Adopt more “audio-adequate” systems as digital players, and/or

- Adopt “higher tier” audio devices (DACs) equipped with appropriate “noise countering” circuitry, and/or

- Adopt additional devices, stacked “in between” the digital player and the DAC to “correct issues” on the go

A super-simple example of type-1 approach is using a battery powered device as digital player: it will infacts apriori have less power-originating noise as it will not require a power transformer (although… careful here: batteries are not totally noise-free either… but let’s not overcomplicate the story now).

Always in the type-1 area: stay away from general purpose PCs, even more so if they are beefed-up gaming rigs. Every single chip on the motherboard is a potential (and effective!) source of EMI/RFI and of time-pacing perturbance.

Even on “simpler hw” machines then gaming rigs the more different stuff the operating system is asking the hw to do while sending data out, the worse for our case. Using an appropriate SBC (Single Board Computer) class device driven by a stripped-down OS where only the essential processes to our special case are kept alive is, barred exceptions and caveats, a technically much healtier – if technically steeper – path to follow for best results given the situation.

A DAC offering the possibility to get power from an independent, audio-quality Power Supply instead of sucking it from the host via the same USB cable used for data is then the first and simplest example of type-2 approach.

DACs capable of inverting the default master-slave USB protocol, and play the “host” role themselves while receiving USB data from the host are another. And so on.

And finally, a number of articles will over time appear on our blog covering devices and accessories of various vendors and types implementing “type-3 approach” at various levels. Stay tuned 🙂